Asked, answered

19/11/12 23:45 Filed in: Business

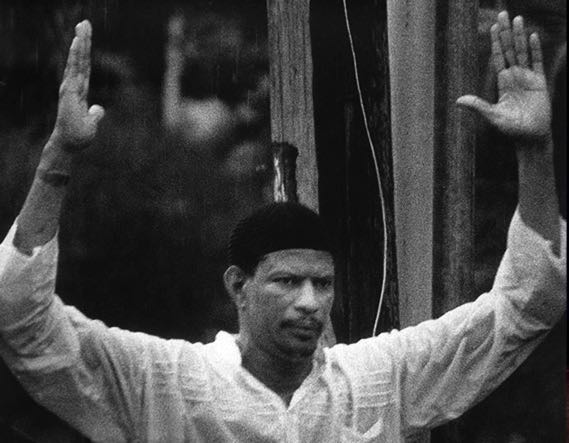

This photograph, scanned from a print, is one of the only images left from my coverage of the 1990 coup attempt.

Zack Arias has an excellent collection of answers to questions put to him online, so popular in fact that he’s gone on break until 2013. I like the idea, but this isn’t an attempt to emulate that impressive work. I do have to long questions put to me by young photographers that I found particularly resonant. Both togs have agreed that I can make a public response to their questions as long as I leave out some identifying information.

AC has a job that requires photography. He successfully arranged with his employers to upgrade the office camera, and to buy some lights and a soft box to improve the in-house photography work they have been doing. The company also paid for AC to attend a course in photography to improve his skills.

Part of his business proposal to the company included getting a cut of the income from this photography work, but since the equipment came in, discussions about revenue sharing have evaporated and other photographers have been brought in to work with the equipment. AC is, unsurprisingly, unhappy with this situation, particularly since the other photographers haven’t been doing particularly good work with the gear.

This situation struck a particularly resonant chord with me.

My career as a photographer essentially began at AMPLE in 1978 when I make the jump one evening from producer to photographer after filling in for an absentee shooter. Until then, I’d only been taking photos to go along with my writing, an entertaining sidebar to my main profession as a writer.

The AMPLE experience put me in the position of delivering on my nascent skills, moving from the occasional good photo to being able to reliably deliver a selection of photos that met client needs.

I would eventually leave AMPLE on bad terms, dissatisfied with several things and angry with the flush indignation of youth, but also departing with the most precious asset the company had invested in over that 24 months, my skill with a camera.

If AC really loves photography, he may find that the situation he’s found himself in might prove to be an equally educational experience. Companies have only one goal really, to make money for their investors. If you aren’t an investor, you’re an employee and your best efforts will be rewarded with a salary, not shares or income participation. Sorry, that’s just how it is.

One of the things that angered me during my time at AMPLE was my feeling that I’d worked really hard for the company, and I expected more than a pay packet as a reward for that commitment.

It took me a really long time to understand that companies aren’t built to make you happy; they are there to pay you a salary. Good companies will do so promptly.

What you extract from an experience with a company really depends on what you intend to draw out of life itself. A company won’t intentionally help you achieve your personal goals, their protestations about “human capital” notwithstanding, but it’s possible to use corporate environments to learn more than you’ll ever manage on your own.

After letting AC know all this using far fewer words, I encouraged him to consider making use of the opportunity the equipment and work situation gives him to build his skills and capabilities. I don’t know what type of business he’s working for, but it sounds like he might be able to find out more about how the company deals with clients for photography and how the process of successful client relations might be pursued.

AC is annoyed and ready to quit, but I think there are possibilities in this situation that are worth exploring before getting to there. Learning while on a salary can be trying, but it’s way better than learning without a regular paycheck. I can attest to that with absolute certainty.

One of the things that AC will also have to live with is the loss of his work done during that time. There are only two times in my life that I’ve worked somewhere as a photographer and in so doing, committed work for hire.

At AMPLE I did a multimedia slideshow (state of the art tech back then) about Carnival that the company funded that’s long since been lost. I mourn some of those photographs, which include my first portraits of Peter Minshall and photographs of his winning band, The Sea.

At the Trinidad Publishing Company, where I served as the first Picture Editor in 1990, my photographs of the 1990 insurrection were lost forever by 1993. Neither body of work was my property and while I often think of those photos, the work that went into them and their value, the photos weren't mine to care for.

Shaun responded to my post about photographic responsibilities with concerns about the challenges of commercial work and mechanical practicalities. He had several issues, so I’ll try to address them one by one.

“…the problem is that for some jobs there’s just hundreds of images of each bottle, each box, each container, at various angles, and it’s quite impossible to get them all edited to perfection in a time frame the client would be happy with.”

I’ve encountered this situation before with local advertising agencies who apparently want to fondle vast numbers of images before settling on exactly the perfect shot. Shaun might want to consider easing off the shutter button a bit to make his workload a bit lighter, but I understand the temptations of large media cards. His solution is a sensible one and was entirely in alignment with my own response to the situation. He batch edits the images to get them to represent his photographic intent and delivers "baked in" TIFF files.

I’m moved to hope that Shaun is concentrating more on effectively licensing the use of his work and crafting suitably prophylactic contract terms rather than worrying about image numbers or the final “look” that the agency imposes on his images.

For many agency situations, the creative teams want to put a stamp on the images that you may not always appreciate or enjoy, but it’s commercial work, not art.

The only useful response to this admittedly frustrating and creatively numb situation is to develop a personal style of imaging that’s attractive and appealing to direct customers and then proceed to market that style to them directly.

“I photographed an event and had the client demand the RAW files after the job. After refusing and going back and forth, I caved and gave them RAW files for their archives but got a signed agreement from them stating that I owned the copyrights and that those RAW files are “for their archives” only and not publication.”

This is a point that I feel very strongly about and my reasons for refusing clients access to RAW files are worth exploring.

Most client’s aren’t aware of file metadata, but RAW files generally only carry camera produced EXIF data, not user generated IPTC information. For that reason, anyone in physical possession of a RAW file can claim to be its author.

Most savvy metadata authors will note that among most camera EXIF data is the serial number of the camera creating the file and if a user has intervened, the name of its owner.

To you I say, if you know that much about RAW files, then you should know why you shouldn’t be releasing them.

From the point of view of quality control, they merge the worst elements of both negatives and transparencies. In the good old day of film, when we handed over a transparency, it was pretty much done as a photo. Negatives allowed for some flexibility in image interpretation. A RAW file is both an original with all the master qualities of a transparency and a malleable data file, with all the appeal of a properly exposed negative.

Someone with access to such a file has a disturbing level of access to the underlying file information you’ve captured and can remake your image in ways you would never have considered.

Again, if you’re being paid well for disposable advertising work, you may not much care about such things, and several of my professional peers have adopted exactly this position.

The only solace I can offer is that over time, it’s unlikely that anyone will have the skill to access and manipulate that RAW file no matter where it ends up. Advertising agencies and corporations simply have better and more productive things to do with their time than to fiddle with RAW images and more useful things to do with their money than to retain the people or the talent to do the same.

That kind of image retentive focus remains the domain of the committed photographer.

If there’s any advice that I can offer that covers the concerns of both young photographers, it’s that they should stick to their knitting and keep working at becoming better photographers.

I always remember Harold Prieto, who was the commanding commercial photographer of the 1980’s evaluating the decision by AMPLE to have an in-house photographer (and in doing so, ensure that he got less work that he might have otherwise).

I’m paraphrasing here, but Harold’s position was basically that if an in-house photographer was any good, he would soon be off on his own and if he wasn’t, he really wasn’t any competition for him.

Over time, that would prove to be true not just for AMPLE, who retained other photographers briefly after I resigned, but also for other advertising agencies who tried the strategy.

At the core of his reasoning was a simple fact. A photographer will always be a photographer and that focus brings its own responsibilities, demands and incentives that simply aren’t fulfilled by a company with an entirely reasonable focus on their return on investment. I could share horror stories about what local print media companies do with the millions of photographs they have captured over the decades, but let's just say that their decisions make perfect sense from a corporate point of view and no sense at all to any serious photographer.

You can make money as a photographer if you work hard enough at it, and you can make money in the advertising agency/creative hotshop/design business if you work hard enough at it, but you really won’t make money or find much satisfaction or fortune in the crazy hybrids that crop up occasionally.

What most folks don’t realize (even some of those running around with cameras recently) is that being a photographer is a truly insane amount of work. It’s a lot of fun and offers a lot of personal fulfilment, but that doesn’t lighten the load of the work and when that hits home, most folks just give up.

I hope Shaun and AC find a path that satisfies them in this business if they choose to pursue it.

blog comments powered by Disqus