BitDepth 803 - October 11

10/10/11 21:55 Filed in: BitDepth - October 2011

Steve Jobs is dead. This is one opinion about why his life mattered.

Why Steve Jobs mattered

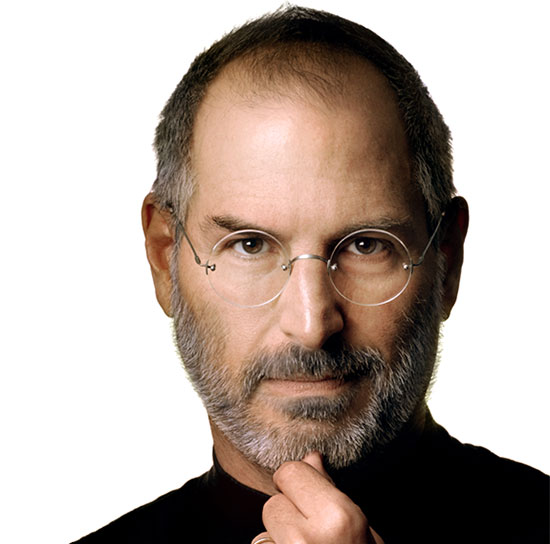

Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple Computer. Photo courtesy Apple Computer.

There were unquestionably as many reasons to dislike Steve Jobs as there were to hold him in adulation. Since he began the resurgence of Apple in 1997 with the iMac, his career and methods have come under almost continuous scrutiny.

According to such reports and biographies, Jobs was a relentless and often apparently undiplomatic taskmaster who demanded excellence of everyone who worked for him and expected the exceptional constantly, sometimes expressing his displeasure with work he deemed to be substandard in blunt terms.

He knew what he wanted, he knew when he didn’t get it and he wasn’t willing to settle for anything less than the realisation of his vision before bringing it to market.

At least some of the post-release buzz around the iPad, for instance, remarked on the surprising fact that the project had been bouncing around Apple for many years, undergoing revision after revision and ultimately awaiting the miniaturisation technologies, battery capacities and hardened glass that the company deployed on its iPhones.

But measuring Steve Jobs’ managerial style is as useless in trying to understand him as trying to divine his romance with jeans and mock turtleneck sweaters.

His real magic, the seductive illusions he turned into reality, began not with a vision of a great product of even a re-imagining of an existing product, it was the unusual clarity of understanding not just how a thing should look, but also how it should work and please its user.

To this day, that special quality remains an elusive one in the technology business.

He might have been a partner in the first successful marketing of a personal computer to the general public, but his real triumph in that space was in looking at the object that had brought him fame and wealth and deciding that it was all wrong.

When he launched in the Macintosh in 1984, he set the precedent for his future in technology. Jobs would not wait for a rival company to make his products irrelevant, he would, like a grandly theatrical Shakespearean character, triumphantly slit the incumbent’s throat on stage while introducing its successor.

Was there any serious techie who heard the original Macintosh introduce itself with a stilting, mechanical “Hello,” who wanted to buy an Apple III?

His taste for such theatrics did not diminish with age. He let Macintosh developers know that their work on OS9 was finished with a coffin onstage at the company’s 2003 developer conference.

Over time, the hiccups between a product’s introduction and its wider adoption after bugs and design errors were ironed out became shorter and shorter until products like the iPhone and iPad roared out of the company’s gates, essentially hits at launch.

Steve Jobs’ eye for the rightness of things did not only flourish at Apple. During his more challenging days at NeXT, the computer company he founded after being ousted from Apple in 1985, he bought the fledgling computer animation division of LucasFilm and after years of trying to market its specialised software and hardware systems, the buzz began about the short animations the newly christened Pixar was producing to show off its capabilities.

By 1995, the company was beginning a popular run of computer rendered animated films, beginning with Toy Story.

Dead a week ago at 56, we are left to ponder not just what he might have done with another two decades, but what he managed to accomplish over much of the five and a half he was granted.

Those who ponder what a post-Jobs Apple will be like should remember that he built the company then returned a decade later, when it had lost its way in corporate hubris, and rebuilt it again, even better. It will be some time before the people at Apple stop asking themselves, “What would Steve do?”

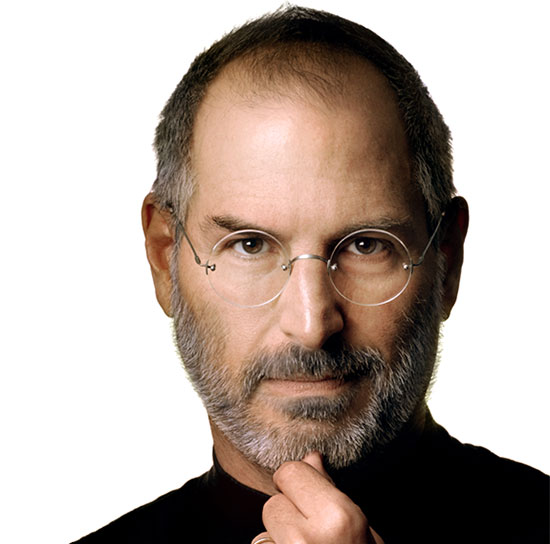

Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple Computer. Photo courtesy Apple Computer.

There were unquestionably as many reasons to dislike Steve Jobs as there were to hold him in adulation. Since he began the resurgence of Apple in 1997 with the iMac, his career and methods have come under almost continuous scrutiny.

According to such reports and biographies, Jobs was a relentless and often apparently undiplomatic taskmaster who demanded excellence of everyone who worked for him and expected the exceptional constantly, sometimes expressing his displeasure with work he deemed to be substandard in blunt terms.

He knew what he wanted, he knew when he didn’t get it and he wasn’t willing to settle for anything less than the realisation of his vision before bringing it to market.

At least some of the post-release buzz around the iPad, for instance, remarked on the surprising fact that the project had been bouncing around Apple for many years, undergoing revision after revision and ultimately awaiting the miniaturisation technologies, battery capacities and hardened glass that the company deployed on its iPhones.

But measuring Steve Jobs’ managerial style is as useless in trying to understand him as trying to divine his romance with jeans and mock turtleneck sweaters.

His real magic, the seductive illusions he turned into reality, began not with a vision of a great product of even a re-imagining of an existing product, it was the unusual clarity of understanding not just how a thing should look, but also how it should work and please its user.

To this day, that special quality remains an elusive one in the technology business.

He might have been a partner in the first successful marketing of a personal computer to the general public, but his real triumph in that space was in looking at the object that had brought him fame and wealth and deciding that it was all wrong.

When he launched in the Macintosh in 1984, he set the precedent for his future in technology. Jobs would not wait for a rival company to make his products irrelevant, he would, like a grandly theatrical Shakespearean character, triumphantly slit the incumbent’s throat on stage while introducing its successor.

Was there any serious techie who heard the original Macintosh introduce itself with a stilting, mechanical “Hello,” who wanted to buy an Apple III?

His taste for such theatrics did not diminish with age. He let Macintosh developers know that their work on OS9 was finished with a coffin onstage at the company’s 2003 developer conference.

Over time, the hiccups between a product’s introduction and its wider adoption after bugs and design errors were ironed out became shorter and shorter until products like the iPhone and iPad roared out of the company’s gates, essentially hits at launch.

Steve Jobs’ eye for the rightness of things did not only flourish at Apple. During his more challenging days at NeXT, the computer company he founded after being ousted from Apple in 1985, he bought the fledgling computer animation division of LucasFilm and after years of trying to market its specialised software and hardware systems, the buzz began about the short animations the newly christened Pixar was producing to show off its capabilities.

By 1995, the company was beginning a popular run of computer rendered animated films, beginning with Toy Story.

Dead a week ago at 56, we are left to ponder not just what he might have done with another two decades, but what he managed to accomplish over much of the five and a half he was granted.

Those who ponder what a post-Jobs Apple will be like should remember that he built the company then returned a decade later, when it had lost its way in corporate hubris, and rebuilt it again, even better. It will be some time before the people at Apple stop asking themselves, “What would Steve do?”

blog comments powered by Disqus