BitDepth 633 - June 23

23/06/08 22:39 Filed in: BitDepth - June 2008

Amazon’s Kindle takes the e-book reader to a new level of sophistication.

Words catch afire

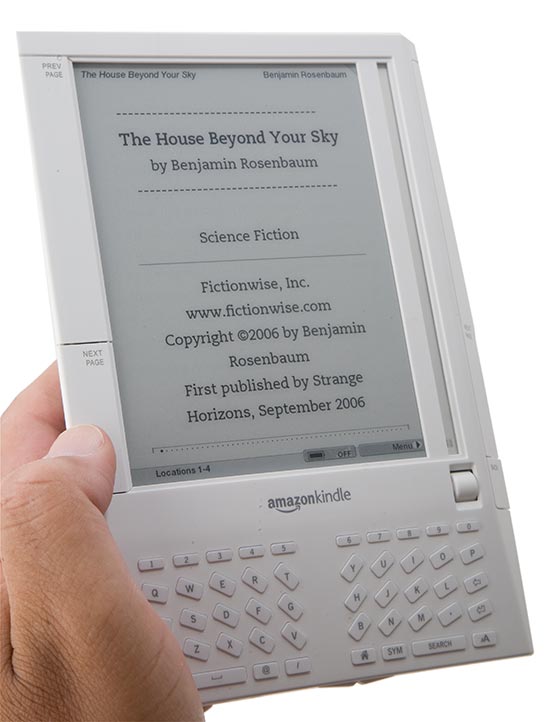

Mike's Kindle was a tempting borrow. The owner plans to convert technical manuals for use on the device for reference on client calls...along with a few books. Photography by Mark Lyndersay.

Amazon's Kindle (US$350) e-book reader is a pleasant surprise, a device that takes more than a few cues from the design playbook of Apple's iPod.

The comparison isn't really unfair, although the two products seem to do very different things. The Kindle and the iPod are both electronic devices that attempt to replace established ways of accessing media. A single iPod can retain the contents of a few shelves worth of CDs and the Kindle, with an added high-capacity SD memory card, can hold a few shelves worth of books.

Both are saddled with Digital Rights Management (DRM) issues that tangle up the potential of hardware and software that go some distance in making e-book reading an effortless experience.

One of the Kindle's great selling points is its wireless connectivity, which allows the device to connect to a special EVDO network that allows a reader to browse the Amazon store, buy a book and download it to the device in just a few minutes.

E-books, which are largely text documents, tend to be much smaller than music files and transfer with lightning speed on even a moderately fast network.

Rubbing sticks together

Nothing like that works in Trinidad and Tobago, so it's a blessing that the Kindle acts like any other USB mass storage device when you connect it to a computer. It simply mounts on the desktop like a big white flash drive, and you can copy compatible files to the appropriate folders on the device.

But "big" doesn't really describe the Kindle very well, and neither do its press photos. The device feels like a slightly oversized paperback book, but even that description doesn't do it justice. It's slim and light, much lighter than the average paperback book and the tapered edges make it even smaller than it actually is. This is a device that you can, without effort, hold in one hand for hours at a time and page forward and back with your thumb if you hold it left hand.

The screen is a mixed bag. It's clear and crisp with minimal ghosting, but there's no backlight, so you'll need to use it with the same lighting that you'd expect to use with a regular book.

Pages scroll with a mild flash as the screen refreshes, but it's only midly disconcerting at first and you get used to it quickly.

If you can get the content you want for the Kindle, it is an extremely convenient, usable alternative to traditional books, particularly for novels that you have no sentimental attachment to.

What works on the Kindle?

The Kindle reads plain text files directly and files in Microsoft Word, HTML and all common graphics format can be sent to Amazon for conversion to Kindle format and plays standard MP3 files natively.

The selection on Amazon that's available to potential local owners without access to a credit card drawn on a US bank is troublingly slim, however. The books that you can access can be purchased and the file will be posted for download.

There are additional sources, however. Many classic novels are available at the Gutenberg Project as text files, though the volunteer nature of the initiative can result in wonky formatting of the documents.

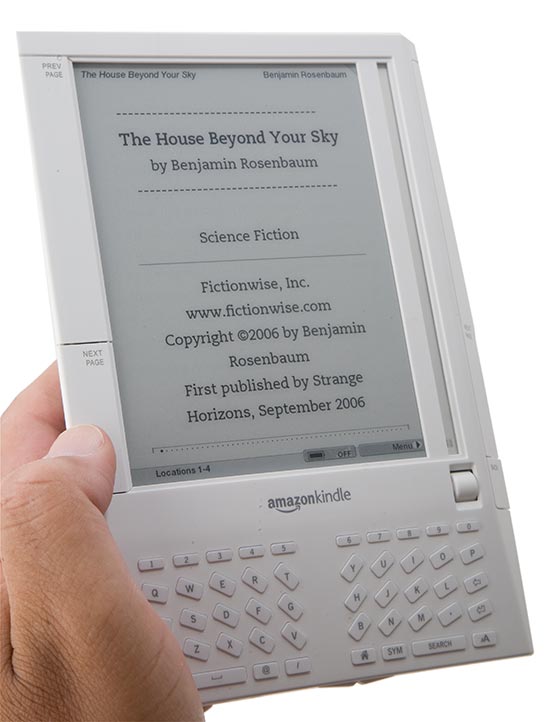

Fictionwise, where I've bought Palm compatible short stories and novellas for years, has upgraded their service to include the Kindle in their comprehensive list of supported e-book formats.

DRMing up the thing

When you bought a book or a CD, there was a fairly limited circle of friends or acquaintances with whom you could share it. Not so with digital files. An MP3 file can zoom around the world to thousands of people in the time it would take to call a friend to brag about the new Gnarls Barkley album.

To limit that potential, publishers now demand that digital content be locked down to the purchaser. In spite of these limitations, the iTunes Store has now surpassed Walmart as a retailer of music and Amazon hopes to grow its resource of books available in digital format.

DRM is a function of both ownership and geography. Publishers like to carve up the world into regions, as evidenced by the region encoding that's long been an irritating aspect of DVD sales, so trying to buy DRM protected music from outside the region tends to be blocked.

It has long been a great irony to me that because of DRM restrictions, the works of VS Naipaul available on Audible, a supplier of downloadable audiobooks recently bought by Amazon, cannot be purchased by a citizen of Trinidad and Tobago.

Mike's Kindle was a tempting borrow. The owner plans to convert technical manuals for use on the device for reference on client calls...along with a few books. Photography by Mark Lyndersay.

Amazon's Kindle (US$350) e-book reader is a pleasant surprise, a device that takes more than a few cues from the design playbook of Apple's iPod.

The comparison isn't really unfair, although the two products seem to do very different things. The Kindle and the iPod are both electronic devices that attempt to replace established ways of accessing media. A single iPod can retain the contents of a few shelves worth of CDs and the Kindle, with an added high-capacity SD memory card, can hold a few shelves worth of books.

Both are saddled with Digital Rights Management (DRM) issues that tangle up the potential of hardware and software that go some distance in making e-book reading an effortless experience.

One of the Kindle's great selling points is its wireless connectivity, which allows the device to connect to a special EVDO network that allows a reader to browse the Amazon store, buy a book and download it to the device in just a few minutes.

E-books, which are largely text documents, tend to be much smaller than music files and transfer with lightning speed on even a moderately fast network.

Rubbing sticks together

Nothing like that works in Trinidad and Tobago, so it's a blessing that the Kindle acts like any other USB mass storage device when you connect it to a computer. It simply mounts on the desktop like a big white flash drive, and you can copy compatible files to the appropriate folders on the device.

But "big" doesn't really describe the Kindle very well, and neither do its press photos. The device feels like a slightly oversized paperback book, but even that description doesn't do it justice. It's slim and light, much lighter than the average paperback book and the tapered edges make it even smaller than it actually is. This is a device that you can, without effort, hold in one hand for hours at a time and page forward and back with your thumb if you hold it left hand.

The screen is a mixed bag. It's clear and crisp with minimal ghosting, but there's no backlight, so you'll need to use it with the same lighting that you'd expect to use with a regular book.

Pages scroll with a mild flash as the screen refreshes, but it's only midly disconcerting at first and you get used to it quickly.

If you can get the content you want for the Kindle, it is an extremely convenient, usable alternative to traditional books, particularly for novels that you have no sentimental attachment to.

What works on the Kindle?

The Kindle reads plain text files directly and files in Microsoft Word, HTML and all common graphics format can be sent to Amazon for conversion to Kindle format and plays standard MP3 files natively.

The selection on Amazon that's available to potential local owners without access to a credit card drawn on a US bank is troublingly slim, however. The books that you can access can be purchased and the file will be posted for download.

There are additional sources, however. Many classic novels are available at the Gutenberg Project

Fictionwise, where I've bought Palm compatible short stories and novellas for years, has upgraded their service to include the Kindle in their comprehensive list of supported e-book formats.

DRMing up the thing

When you bought a book or a CD, there was a fairly limited circle of friends or acquaintances with whom you could share it. Not so with digital files. An MP3 file can zoom around the world to thousands of people in the time it would take to call a friend to brag about the new Gnarls Barkley album.

To limit that potential, publishers now demand that digital content be locked down to the purchaser. In spite of these limitations, the iTunes Store has now surpassed Walmart as a retailer of music and Amazon hopes to grow its resource of books available in digital format.

DRM is a function of both ownership and geography. Publishers like to carve up the world into regions, as evidenced by the region encoding that's long been an irritating aspect of DVD sales, so trying to buy DRM protected music from outside the region tends to be blocked.

It has long been a great irony to me that because of DRM restrictions, the works of VS Naipaul available on Audible, a supplier of downloadable audiobooks recently bought by Amazon, cannot be purchased by a citizen of Trinidad and Tobago.

blog comments powered by Disqus