BitDepth#844 - July 24

23/07/12 19:26 Filed in: BitDepth - July 2012

John Barry created some of the most memorable scores for the James Bond series, but he didn't write the notes of the famous theme that link back to Trinidad and Tobago.

The other JB

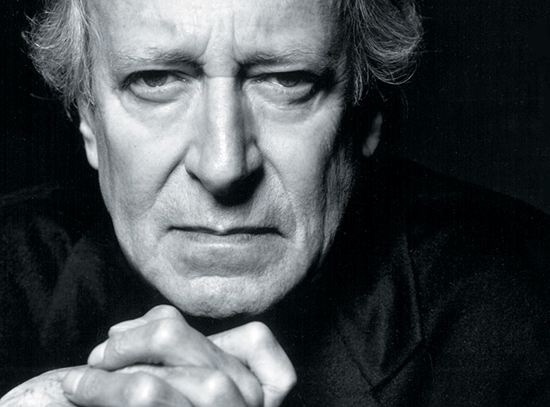

John Barry, composer of 96 film scores.

This year, the James Bond franchise turns 50 and the clearest connection between that and our upcoming Independence celebrations is the presence of a Trini thread through the director’s chair of Sam Mendes for the latest instalment, Skyfall. Mendes is the grandson of Trinidadian writer Alfred Mendes and the son of Trinidad-born Jameson Mendes.

But the influence of Trinidad and Tobago begins much earlier than that for Bond, with the man who was first hired to compose a score for a Bond film, Monty Norman.

Norman composed the exciting sting played by surf guitarist Vic Flick that’s become a signature moment in every film since it was introduced in Dr No.

John Barry, whose work otherwise defines the series, wrote the familiar orchestrations that accompanied Norman’s work and the two men’s contributions to the familiar theme ended in a court battle over authorship.

Norman would successfully argue his case by referencing a prior use of the familiar chord progression as the basis of a song, “Good sign, Bad sign,” he'd written for a musical version of VS Naipaul’s A house for Mr Biswas.

So there you have it. One of the most recognisable fragments of music in modern cinematic history was inspired by, yes, Trinidad and Tobago.

But that’s not all there was from this country on that first soundtrack. Much of the music for that first film was played by Byron Lee and the Dragonnaires, including a calypso number called “Jump up,” typical of the type of pop calypso that was played then in Barbados and Jamaica.

This isn't the first time this has happened, by the way. The first Jamaican Independence music theme was composed and sung by Lord Creator, a Trinidadian calypsonian whose work appears twice on the Jamaican Independence compilation album.

From those beginnings, the sweeping orchestrations of British composer John Barry would take over the series. Barry would score an unrivalled eleven Bond films, putting his stamp on six consecutive films from From Russia with Love to Diamonds are Forever.

In those eight years, Barry’s sweeping strings and brassy horn blasts would create a tapestry of sound that would define the score as one of most identifiable characteristics of a Bond film.

Barry created many stings and cues in those films that still appear in the Bond films of this century. On the soundtrack albums, you’ll find the instantly recognisable drama of “007,” which would drive action appearances of the not particularly secret agent and the surreal flutter of “Capsule in Space,” which would find echoes through underwater and space scenes.

Film scores are an unusual art. When image and music work in perfect sync, you’re hardly aware of the melodies at all. The individual passages of music, called cues, hint at the emotion of the scene, adding information that the two dimensional nature of cinema can’t always effectively convey.

In his work for films like Born Free, Dances with Wolves and Out of Africa, which all won Academy awards for John Barry, the scores buoy the visuals dramatically, often lifting scenes to powerful effect.

The Bond films were something different. Over the course of his first six Bond films, Barry defined a different role for his score, that of a co-star with its own character and role.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the first film to try to replace Sean Connery.

It’s a surprisingly good film that just happens to have an unskilled actor in the lead role, and it also has one of the most remarkable scores of the whole series. Connery replacement George Lazenby might have faltered, but Barry did not, producing a score with so many dramatic cues that its influence still echoes throughout the series.

The only serious effort at an alternative Bond film, Never say Never again, stands as testimony to what happens when you do Bond without Barry. Despite having a strong script (a court restricted rewrite of Thunderball) a great Bond girl in the young Kim Basinger and the best Bond himself, a seasoned and gritty Sean Connery, what resulted, without John Barry’s distinctive cues and stings, was a movie with a guy named James in it, but not a Bond film at all.

Barry’s work influenced David Arnold, who produced 1997’s homage album, Shaken and Stirred (you must hear the Propellerheads' version of the theme from OHMSS), which won him the role of composer on the five most recent Bond films.

The newest Bond film introduces a new composer, Thomas Newman who works closely with Sam Mendes, but like Marvin Hamlisch and Bill Conti before him, he will find himself working with the long established presence of Barry’s work on the series. If he’s smart (Eric Serra wasn’t on Goldeneye), he’ll take advantage of it.

John Barry, composer of 96 film scores.

This year, the James Bond franchise turns 50 and the clearest connection between that and our upcoming Independence celebrations is the presence of a Trini thread through the director’s chair of Sam Mendes for the latest instalment, Skyfall. Mendes is the grandson of Trinidadian writer Alfred Mendes and the son of Trinidad-born Jameson Mendes.

But the influence of Trinidad and Tobago begins much earlier than that for Bond, with the man who was first hired to compose a score for a Bond film, Monty Norman.

Norman composed the exciting sting played by surf guitarist Vic Flick that’s become a signature moment in every film since it was introduced in Dr No.

John Barry, whose work otherwise defines the series, wrote the familiar orchestrations that accompanied Norman’s work and the two men’s contributions to the familiar theme ended in a court battle over authorship.

Norman would successfully argue his case by referencing a prior use of the familiar chord progression as the basis of a song, “Good sign, Bad sign,” he'd written for a musical version of VS Naipaul’s A house for Mr Biswas.

So there you have it. One of the most recognisable fragments of music in modern cinematic history was inspired by, yes, Trinidad and Tobago.

But that’s not all there was from this country on that first soundtrack. Much of the music for that first film was played by Byron Lee and the Dragonnaires, including a calypso number called “Jump up,” typical of the type of pop calypso that was played then in Barbados and Jamaica.

This isn't the first time this has happened, by the way. The first Jamaican Independence music theme was composed and sung by Lord Creator, a Trinidadian calypsonian whose work appears twice on the Jamaican Independence compilation album.

From those beginnings, the sweeping orchestrations of British composer John Barry would take over the series. Barry would score an unrivalled eleven Bond films, putting his stamp on six consecutive films from From Russia with Love to Diamonds are Forever.

In those eight years, Barry’s sweeping strings and brassy horn blasts would create a tapestry of sound that would define the score as one of most identifiable characteristics of a Bond film.

Barry created many stings and cues in those films that still appear in the Bond films of this century. On the soundtrack albums, you’ll find the instantly recognisable drama of “007,” which would drive action appearances of the not particularly secret agent and the surreal flutter of “Capsule in Space,” which would find echoes through underwater and space scenes.

Film scores are an unusual art. When image and music work in perfect sync, you’re hardly aware of the melodies at all. The individual passages of music, called cues, hint at the emotion of the scene, adding information that the two dimensional nature of cinema can’t always effectively convey.

In his work for films like Born Free, Dances with Wolves and Out of Africa, which all won Academy awards for John Barry, the scores buoy the visuals dramatically, often lifting scenes to powerful effect.

The Bond films were something different. Over the course of his first six Bond films, Barry defined a different role for his score, that of a co-star with its own character and role.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the first film to try to replace Sean Connery.

It’s a surprisingly good film that just happens to have an unskilled actor in the lead role, and it also has one of the most remarkable scores of the whole series. Connery replacement George Lazenby might have faltered, but Barry did not, producing a score with so many dramatic cues that its influence still echoes throughout the series.

The only serious effort at an alternative Bond film, Never say Never again, stands as testimony to what happens when you do Bond without Barry. Despite having a strong script (a court restricted rewrite of Thunderball) a great Bond girl in the young Kim Basinger and the best Bond himself, a seasoned and gritty Sean Connery, what resulted, without John Barry’s distinctive cues and stings, was a movie with a guy named James in it, but not a Bond film at all.

Barry’s work influenced David Arnold, who produced 1997’s homage album, Shaken and Stirred (you must hear the Propellerheads' version of the theme from OHMSS), which won him the role of composer on the five most recent Bond films.

The newest Bond film introduces a new composer, Thomas Newman who works closely with Sam Mendes, but like Marvin Hamlisch and Bill Conti before him, he will find himself working with the long established presence of Barry’s work on the series. If he’s smart (Eric Serra wasn’t on Goldeneye), he’ll take advantage of it.

blog comments powered by Disqus