BitDepth 722 - March 16

15/03/10 23:46 Filed in: BitDepth - March 2010

Photoshop turns 20 long after it became a noun and a verb that described the extensive photomanipulation it was capable of.

Two decades of Photoshop

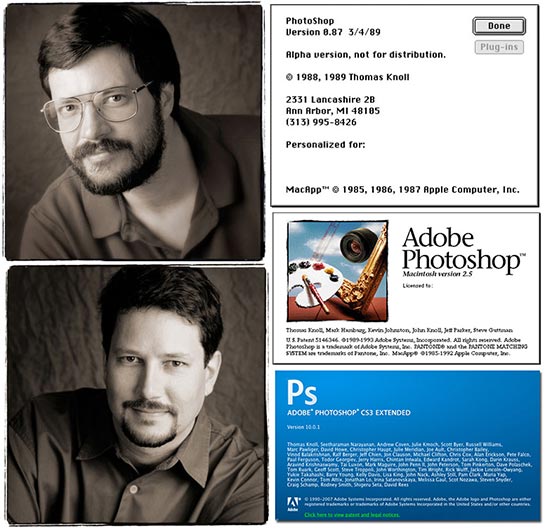

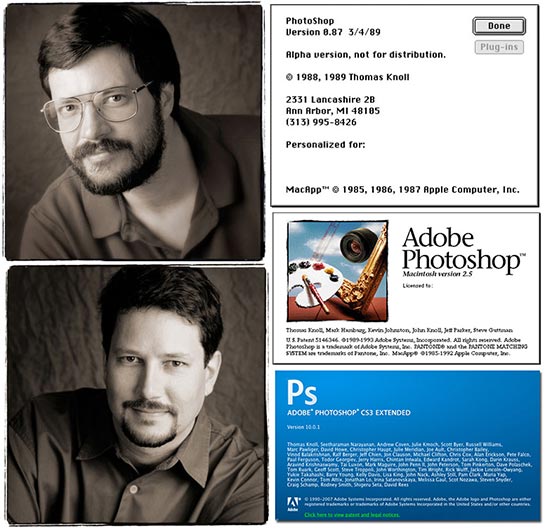

The brothers Knoll, Thomas at top, John below, and the splash screens of three pivotal Photoshop releases. Photoshop .87 lay between Barneyscan and Adobe, version 2.5 was the first release considered to be usable for production work and Photoshop CS3 brought Intel native code to the Mac platform.

When people think of software, they think of commonplace tools like Microsoft’s Office, but before Word and Excel, there were word processors and spreadsheets, before there was Photoshop, there was only the analog void.

I’ll always remember the first time I saw the software at work. Michael Haynes, then a Guardian ‘management trainee,’ was removing a scratch from a scanned photo with some quick mouse clicks.

I stood behind him, mouth agape. Doing anything like that, in my experience, required fine sable brushes, careful mixing of colours and a staggering level of patience.

Haynes was doing hours of work in seconds and I watched the world of photography that I knew evaporate.

Right up until that moment, I had only been paying tangential attention to all the equipment that Alwin Chow had been installing gleefully around the Guardian. Haynes’ demo changed that.

Part of that gear was one of the 200 Barneyscan scanners ever sold, a cranky, bulky device set up on the boundary of the paper’s advertising and production departments.

I’d spent a few hours using the software, scanning on a Mac Classic which had a black and white monitor. The Barneyscan software dithered the image, rendering faux continuous tone images on a screen with all the photographic characteristics of fax paper.

Somewhere in a box at the Guardian is a rare copy of that Barneyscan floppy, software created by two brothers, Thomas and John Knoll. In less than a year, they would create a new version that they called Photoshop and show it to Adobe.

In the 20 years since, that floppy disk’s worth of software code has, in very fundamental ways, changed the world. The product’s name has become a verb and an adjective, used to describe fundamental changes to a digital image.

Along the way, the software has filled a digital graveyard with the dead products that tried to unseat it as the image manipulation product of choice.

Nobody is likely to remember Letraset’s Color Studio, SuperMac’s PixelPaint, Silicon Beach’s quite agreeable and photographer focused Digital Darkroom, or bold experiments like Macromedia’s XRes and HSC Software’s Live Picture which tried to work around the limitations of old, slow hardware by delaying the rendering of corrections to the end of a project.

Photoshop’s developers kept tweaking the product to work on the hardware available while adding to the deep features of the product.

At least part of the secret of Photoshop’s longevity is the sheer depth of the software. I’ve been working with it for 20 years now, and there are parts of it that I still shy away from.

Some of that richness is simply a long programming legacy. Until the seventh version, the product was very much a production tool. By then, Adobe realised just how many photographers were using their product and began adding photo-friendly features like an image browser and RAW file support.

The company now offers a special ‘extended’ version, with specialist tools for filmmakers, 3D animators and medical professionals. Adobe has extended Photoshop’s reach with products like Lightroom, which was designed expressly for photographers, Elements, which puts a pretty face on Photoshop’s power and cuts the price by 80 per cent for home users and even a free web application with image galleries.

Twenty years on, Adobe Photoshop remains the 800 pound gorilla in the digital realm and its programmers are still prepared to snarl menacingly when rivals enter the room.

Find out about Adobe Photoshop here...

View Photoshop imagery gone wrong here...

Learn about Photoshop here...

The brothers Knoll, Thomas at top, John below, and the splash screens of three pivotal Photoshop releases. Photoshop .87 lay between Barneyscan and Adobe, version 2.5 was the first release considered to be usable for production work and Photoshop CS3 brought Intel native code to the Mac platform.

When people think of software, they think of commonplace tools like Microsoft’s Office, but before Word and Excel, there were word processors and spreadsheets, before there was Photoshop, there was only the analog void.

I’ll always remember the first time I saw the software at work. Michael Haynes, then a Guardian ‘management trainee,’ was removing a scratch from a scanned photo with some quick mouse clicks.

I stood behind him, mouth agape. Doing anything like that, in my experience, required fine sable brushes, careful mixing of colours and a staggering level of patience.

Haynes was doing hours of work in seconds and I watched the world of photography that I knew evaporate.

Right up until that moment, I had only been paying tangential attention to all the equipment that Alwin Chow had been installing gleefully around the Guardian. Haynes’ demo changed that.

Part of that gear was one of the 200 Barneyscan scanners ever sold, a cranky, bulky device set up on the boundary of the paper’s advertising and production departments.

I’d spent a few hours using the software, scanning on a Mac Classic which had a black and white monitor. The Barneyscan software dithered the image, rendering faux continuous tone images on a screen with all the photographic characteristics of fax paper.

Somewhere in a box at the Guardian is a rare copy of that Barneyscan floppy, software created by two brothers, Thomas and John Knoll. In less than a year, they would create a new version that they called Photoshop and show it to Adobe.

In the 20 years since, that floppy disk’s worth of software code has, in very fundamental ways, changed the world. The product’s name has become a verb and an adjective, used to describe fundamental changes to a digital image.

Along the way, the software has filled a digital graveyard with the dead products that tried to unseat it as the image manipulation product of choice.

Nobody is likely to remember Letraset’s Color Studio, SuperMac’s PixelPaint, Silicon Beach’s quite agreeable and photographer focused Digital Darkroom, or bold experiments like Macromedia’s XRes and HSC Software’s Live Picture which tried to work around the limitations of old, slow hardware by delaying the rendering of corrections to the end of a project.

Photoshop’s developers kept tweaking the product to work on the hardware available while adding to the deep features of the product.

At least part of the secret of Photoshop’s longevity is the sheer depth of the software. I’ve been working with it for 20 years now, and there are parts of it that I still shy away from.

Some of that richness is simply a long programming legacy. Until the seventh version, the product was very much a production tool. By then, Adobe realised just how many photographers were using their product and began adding photo-friendly features like an image browser and RAW file support.

The company now offers a special ‘extended’ version, with specialist tools for filmmakers, 3D animators and medical professionals. Adobe has extended Photoshop’s reach with products like Lightroom, which was designed expressly for photographers, Elements, which puts a pretty face on Photoshop’s power and cuts the price by 80 per cent for home users and even a free web application with image galleries.

Twenty years on, Adobe Photoshop remains the 800 pound gorilla in the digital realm and its programmers are still prepared to snarl menacingly when rivals enter the room.

Find out about Adobe Photoshop here...

View Photoshop imagery gone wrong here...

Learn about Photoshop here...

blog comments powered by Disqus