BitDepth 479 - June 28

11/01/09 17:43 Filed in: BitDepth - June 2005

Thinking about about the future of photography.

The image as hero

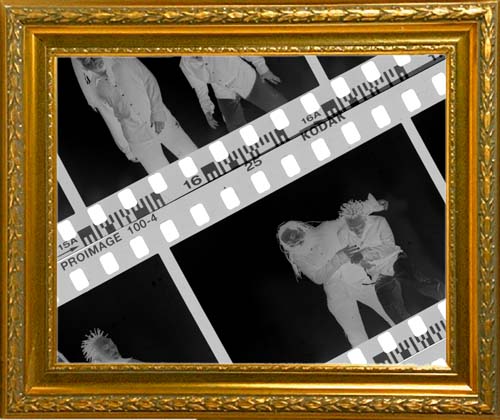

It's the image, stupid. Film or pixels, what we look for is the content, not the medium. Image by Mark Lyndersay.

It was a chore I'd been ducking for years now, or so I thought. A week ago, I finally grit my teeth, pulled a dust mask over my face and began heaving junk out of a room in which I'd once spent whole weeks of my life.

This wasn't a chore, but it was a commemoration of the highwater mark for a tide that was now out forever.

The warning sign was long gone from the door, but it had been years since anyone, least of all me, had called this sealed space a darkroom.

I picked up packages of D76 and Dektol, chemicals that once were swords in my photographic scabbard, but now seemed ancient, browned with age. The plastic tanks and reels whose longevity had once been a niggling worry now mocked my fears with their evident invincibility.

Not only had they not failed at a crucial moment, they had managed to outlive their time, grooved plastic circles that defied not only the hundreds of rolls of film they had processed and gallons of chemistry poured over them but even my cavalier neglect these past six years.

Dust and dead bugs covered all of it. The technologies that had birthed my interest in photography now lingered defiantly in their obsolescence, flipping me a chemical stained finger, worthless junk that I still can't bear to toss out.

So I toss most of the chemicals (not the toner, that's poison, or the Diafine, that's impossible to find now) and stack the trays and tanks together after wiping the crud off them.

I'm not the only one cleaning photo house. Kodak announced quietly last week that it was ending sales of its black and white printing paper in calls to trade journalists. The paper, which had once been the market leader among the stained tongs set, was no longer a viable product in the market. From 2006, Ilford and the other small specialty shops will have that dwindling market to themselves.

Cleaning the darkroom wasn't only a long overdue job, it was also an admission that hundreds of negatives shot between 1996, when I started consulting with newspapers more than shooting, and 2001, when I stopped shooting film entirely, were never going to be proofed or printed.

Their next life would be digital and rescuing them from the grime and cleaning them was the first step in preparing them for scanning.

It was at that point, cleaning rag in one hand, a stack of negatives in the other and impossible stacks of rubbish before me, that I realised that even in retrospect, negatives and prints were only the beginning of what photography meant to me now.

In this digital age, they were curious relics, artifacts of silver and dye that awaited transformation in a new medium, one in which they could live a fuller, more useful life.

As I wrote those words, I glanced up the printer I've hooked up to my laptop, a device that exists only to satisfy customers of my photography and is otherwise useless to me. I've printed pictures to pin to my walls, to stoke conversations and generated proofs and final prints from it, but I've never actually printed a single image on it for fun.

Getting a great print out of it doesn't sing with siren magic the way Seagull's Oriental did as the image slowly appeared, tinged orange-red under the safelight, floating to the surface of the exhausted browns of developer.

It takes work to make a good print from it. I still make test strips like I did with multigrade photo papers to fine tune the image and tweak it to its best, but it's a machine that hums quietly and spits the paper out with an effortless, vaguely snobbish whine. It doesn't slosh around and give the paper a slippery hard to grip surface. It isn't... organic.

Now that people can make perfectly decent photographs with their phones (as long as they have those still-rare 2 megapixel cells), the value of the image as an artifact of reality dims as it becomes more accessible. You can show twenty people your dog's new puppies in a matter of minutes with a digital camera and e-mail, and that makes the one-hour lab seem achingly antediluvian. You can even look at those phone images on the cell itself or import a digital wallet full of images of the kids to bore people in a whole new medium.

The next evolution of photography, from dyes to pixels, liberates images from physical space and sets them free in the virtual world of the many devices that can transfer and display them.

For consumers of photography, it's a vast playground, as even the most casual of probes on Google's image search will show. For photographers, it's a more difficult world, one in which control becomes more difficult and competition is global. I remain curious about what comes next.

Bonus note

I'd been away from printing images for a while, both on in the darkroom and from my computer, so I was surprised to find how much the landscape of colour printers had changed.

The last time I bought a colour inkjet printer, it was 1997 and Epson ruled the roost. Almost ten years later, there is a vast assortment of colour printers, speciality papers and inks that rivals the most enthusiastic era of the darkroom.

This is hardly a scientific break-out, but I find that generally, the colour printer market divides like this...

Epson. Still, the best for graphics professionals and photographers enamoured of the electric colours of Fujichrome and Cibachrome. Their best printers have a tendency to "bronzing", a metallic reflection in areas of subtle tonal change that's disturbing in scenes that are primarily organic.

HP remains the best bet for all-round business printing. Colour photos look good and are dramatically improved, but aren't as rich or finely detailed as the competition. Fast and clean on plain paper with text and minimal graphics.

Canon. The surprise of the 2005 market. Cheaper inks and printers than Epson with a colour palette that recalls the warm richness of the old Kodak Vericolor film and paper combination.

I chose the Canon IP6000 and I've had startlingly good results with Ilford's inkjet paper, which takes Canon's inks as if it were made specially for it.

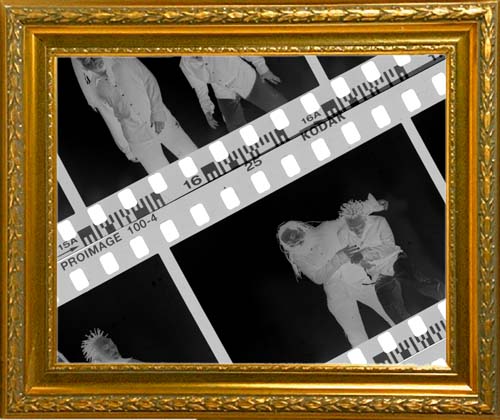

It's the image, stupid. Film or pixels, what we look for is the content, not the medium. Image by Mark Lyndersay.

It was a chore I'd been ducking for years now, or so I thought. A week ago, I finally grit my teeth, pulled a dust mask over my face and began heaving junk out of a room in which I'd once spent whole weeks of my life.

This wasn't a chore, but it was a commemoration of the highwater mark for a tide that was now out forever.

The warning sign was long gone from the door, but it had been years since anyone, least of all me, had called this sealed space a darkroom.

I picked up packages of D76 and Dektol, chemicals that once were swords in my photographic scabbard, but now seemed ancient, browned with age. The plastic tanks and reels whose longevity had once been a niggling worry now mocked my fears with their evident invincibility.

Not only had they not failed at a crucial moment, they had managed to outlive their time, grooved plastic circles that defied not only the hundreds of rolls of film they had processed and gallons of chemistry poured over them but even my cavalier neglect these past six years.

Dust and dead bugs covered all of it. The technologies that had birthed my interest in photography now lingered defiantly in their obsolescence, flipping me a chemical stained finger, worthless junk that I still can't bear to toss out.

So I toss most of the chemicals (not the toner, that's poison, or the Diafine, that's impossible to find now) and stack the trays and tanks together after wiping the crud off them.

I'm not the only one cleaning photo house. Kodak announced quietly last week that it was ending sales of its black and white printing paper in calls to trade journalists. The paper, which had once been the market leader among the stained tongs set, was no longer a viable product in the market. From 2006, Ilford and the other small specialty shops will have that dwindling market to themselves.

Cleaning the darkroom wasn't only a long overdue job, it was also an admission that hundreds of negatives shot between 1996, when I started consulting with newspapers more than shooting, and 2001, when I stopped shooting film entirely, were never going to be proofed or printed.

Their next life would be digital and rescuing them from the grime and cleaning them was the first step in preparing them for scanning.

It was at that point, cleaning rag in one hand, a stack of negatives in the other and impossible stacks of rubbish before me, that I realised that even in retrospect, negatives and prints were only the beginning of what photography meant to me now.

In this digital age, they were curious relics, artifacts of silver and dye that awaited transformation in a new medium, one in which they could live a fuller, more useful life.

As I wrote those words, I glanced up the printer I've hooked up to my laptop, a device that exists only to satisfy customers of my photography and is otherwise useless to me. I've printed pictures to pin to my walls, to stoke conversations and generated proofs and final prints from it, but I've never actually printed a single image on it for fun.

Getting a great print out of it doesn't sing with siren magic the way Seagull's Oriental did as the image slowly appeared, tinged orange-red under the safelight, floating to the surface of the exhausted browns of developer.

It takes work to make a good print from it. I still make test strips like I did with multigrade photo papers to fine tune the image and tweak it to its best, but it's a machine that hums quietly and spits the paper out with an effortless, vaguely snobbish whine. It doesn't slosh around and give the paper a slippery hard to grip surface. It isn't... organic.

Now that people can make perfectly decent photographs with their phones (as long as they have those still-rare 2 megapixel cells), the value of the image as an artifact of reality dims as it becomes more accessible. You can show twenty people your dog's new puppies in a matter of minutes with a digital camera and e-mail, and that makes the one-hour lab seem achingly antediluvian. You can even look at those phone images on the cell itself or import a digital wallet full of images of the kids to bore people in a whole new medium.

The next evolution of photography, from dyes to pixels, liberates images from physical space and sets them free in the virtual world of the many devices that can transfer and display them.

For consumers of photography, it's a vast playground, as even the most casual of probes on Google's image search will show. For photographers, it's a more difficult world, one in which control becomes more difficult and competition is global. I remain curious about what comes next.

Bonus note

I'd been away from printing images for a while, both on in the darkroom and from my computer, so I was surprised to find how much the landscape of colour printers had changed.

The last time I bought a colour inkjet printer, it was 1997 and Epson ruled the roost. Almost ten years later, there is a vast assortment of colour printers, speciality papers and inks that rivals the most enthusiastic era of the darkroom.

This is hardly a scientific break-out, but I find that generally, the colour printer market divides like this...

Epson. Still, the best for graphics professionals and photographers enamoured of the electric colours of Fujichrome and Cibachrome. Their best printers have a tendency to "bronzing", a metallic reflection in areas of subtle tonal change that's disturbing in scenes that are primarily organic.

HP remains the best bet for all-round business printing. Colour photos look good and are dramatically improved, but aren't as rich or finely detailed as the competition. Fast and clean on plain paper with text and minimal graphics.

Canon. The surprise of the 2005 market. Cheaper inks and printers than Epson with a colour palette that recalls the warm richness of the old Kodak Vericolor film and paper combination.

I chose the Canon IP6000 and I've had startlingly good results with Ilford's inkjet paper, which takes Canon's inks as if it were made specially for it.

blog comments powered by Disqus